Current Pediatric Research

International Journal of Pediatrics

Malnutrition and associated factors among under five children (6-59 Months) at Shashemene Referral Hospital, West Arsi Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia.

Zemenu Yohannes Kassa*, Tsigereda Behailu, Alemu Mekonnen, Mesfine Teshome, Sintayehu Yeshitila

Hawassa University, College of Medicine and Health sciences, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Hawassa, South Ethiopia

- Corresponding Author:

- Zemenu Yohannes Kassa

Hawassa University

College of Medicine and Health Sciences

School of Nursing and Midwifery, Hawassa

1560, South Ethiopia

Tel: +251-920-315-430

E-mail: zemenu2013@gmail.com

Accepted date: January 31, 2017

Background: Malnutrition is alarmingly decreasing the two-decade, but still major public health problems in the world, especially in developing countries, include Ethiopia. Stunning and wasting rates are dropping, but 159 million and 50 million children around the world still affected respectively. Malnutrition in Ethiopia in the form of stunting, underweight and wasting were as 44%, 29% and 10% and Oromia national region state 44.1%, 39.6% and 12.5%, respectively under five children. Objective: the aim of this study is to assess magnitude of malnutrition and associated factors among under-five children in Shashamene Referral Hospital, Oromia Ethiopia, 2016. Method: Facility based cross-sectional design was conducted. Systematic random sampling technique was used. After data collection SPSS 20.0 was employed for data entry, organize and analysis. Odd ratio and p value were computed to identify the presence and strength of association and <0.05 stastical significance was declared. Results: The magnitude of stunting, underweight and wasting were about 38.3%, 49.2% and 25.2 %, respectively. Educational status of mother and child age was significantly associated with stunting. Complementary food was associated with underweight and occupation of mother was associated with wasting. Conclusion and recommendation: This study revealed that malnutrition was high than the regional and national figures found from Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey 2011. Community based nutrition program need to be established to tackle the problem of malnutrition at community level depending on the severity of malnutrition identified in this study. Nutrition education by health extension works need to be strengthening to improving the feeding practice of parents on appropriate children feeding.

Keywords

Malnutrition, Under-five in Ethiopia

Introduction

Malnutrition is alarmingly decreasing the two-decade, but still major public health problems in the world, especially in developing countries, include Ethiopia. Stunning and wasting rates are dropping but 159 million and 50 million children around the world still affected respectively [1]. Malnutrition is attributed one third of under-five death in the first five years of live, which is preventable by economic growth [2]. Globally, one out of every 13 children were wasted, which is 16 million children were severely wasted [1].Children malnutrition affects academic performance, physical and mental development throughout their lives [2,4]. Under-five malnutrition is an indicator of one’s counties health status as well as economic conditions [5]. Malnutrition among children is a critical problem because its effects are long lasting and go beyond childhood. It has both short and long term consequences [6,7]. Malnutrition especially under five still devastating problems in developing countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, including Ethiopia [8]. Stunting, wasting, and underweight are among those anthropometric indicators are commonly used to measure malnutrition of under five children. Underweight (low weight-for-age) reflects both low height-for-age and low weight-for-age and therefore reflects both cumulative and acute exposures of malnutrition [9]. Ethiopia has a high prevalence of Acute and chronic malnutrition, with almost half of Ethiopian children chronically malnourished and one-inten children wasted. About 47% of children under-five are stunted, 11% are wasted and 38% are underweight [10]. Epidemiological studies were conducted in developing countries have identified several factors associated with under nutrition, including low parental education, poverty, low maternal intelligence, food insecurity, rural residence and sub-optimal infant feeding practices [4,11]. Nearly half of death under-five is attributable by malnutrition. Malnutrition puts children at greater risk of dying from common infections, increases the infection and delayed recovery. Poor nutrition in the first 1,000 days of a child’s life can also lead to stunted growth, which is irreversible and associated with impaired cognitive ability and reduced school and work performance [12]. An estimated 53% of infection death is the effect of malnutrition on diseases such as measles, pneumonia, and diarrhea [13,14]. Underweight and stunting rates among young children are the highest in sub-Saharan Africa. About two in five children (38%) are underweight, 10.5% of the children are wasted (2.2% are severely wasted) and 46.5% of the children are stunted that half of them are severely stunted [15]. Malnutrition in Ethiopia is serious and 44% of children were stunted, 10% wasted and 29% underweight with wide regional variations [16-18].

Methods and Materials

The study was conducted in Shashemane Referral Hospital from April 1 to May 24, 2016.Shashemane Referral Hospital is located about 240 km from the capital, Addis Ababa. It is one of the hospitals that provide health service including screening for malnutrition in Shashemene and surrounding area. The study population were systematically selected under-five children and their caregivers who utilize under-five OPD at Shashemane Referral Hospital. Children under five years of age, who were visit the OPD at Shashemane referral Hospital and their care givers (mother, foster who live with the child at least for 6 months), were interviewed. Children who are severely ill and admitted were excluded. Facility based cross sectional was employed .The sample size was determine by using single population proportion with 95% confidence interval and marginal error of 5%, by taking a maximum value of 50%.The required sample sized was 384. Non response rate of 10% that means 38 sample sizes was added. The total sample size was 422.

Shashemene referral hospital was selected by simple random sampling methods. The number of Under five children who have been attended an under five OPD were counted for the last six consecutive month and found to be 2350, then we were taken average two month divided by total sample size 422 to get “K” value. Then K equal to 5.6. The first day was started arbitrarily, then proceed every “6” value. Then, the data was collected daily every 6 under five OPD patients until the total sample size was finished. Pre-tested an anonymous interviewed structured questionnaires were prepared after reviewing different relevant literatures. The questionnaires were first prepared in English and then translated to Amharic, the local language of the respondents in the study area. The questionnaires were administered to all under five OPD patients during the data collection period, and who met the inclusion.

Anthropometric Measurements

Length was taken for those less than two years old children in recumbent position and the height for those above two years children in erect position. Measurement of height (length) was done in a lying position with wooden board for children of age under two years (below 85 cm) and for children above two years stature will be measured in a standing position in centimeters to the nearest of 0.1 cm. The weight was taken using the weighing scale. For those children who can’t stand weighed with their mother and the mother’s weight was subtracted. The weighing scale was adjusted before each measurement. Weight was measured with minimum clothing and no shoes using a weighing scale in kg to the nearest of 0.1 kg. Only children under 110 cm (proxy for 5 year) and over 65 cm (proxy for 6 month will be questioned to ascertain age using detail season calendar and the presence or absence of pitting edema was checked by pressing child’s foot bilaterally.

Weight-for-Age

Reflects body mass relative to chronological age; Often used if the child is normal, under or over weight. It is a simple index but does not consider height. It is influenced by both the height (height-for-age) and weight (weightfor- height) of a child and its composite nature makes interpretation complex. For example, weight-for-age fails to distinguish between short children of adequate body weight and tall, thin children.

Weight-for-Height

Reflects body mass relative to height; It is a measure of acute or short term exposure to a negative environment. It is sensitive to calorie intake or the effects of disease. Wasting (thinness) reflects a deficit in tissue and fat mass and indicates that the child don’t weigh as much as they should for their height. In most cases a recent and severe process of weight loss, which is often associated with acute starvation and/or severe disease. It is the first response to nutritional and/or infectious insult.

Height-for-Age

Reflects height relative to chronological age; It is used to tell if a child is the normal height for age. Stunted growth (shortness) reflects failure to reach linear growth potential (pre and postnatal) as a result of sub-optimal health or nutritional conditions. On a populationwide basis, high levels of stunting are associated with poor socio-economic conditions and increased risk of frequent and early exposure to adverse conditions such as illness and/or inappropriate feeding practices. It is assumed to indicate long term, cumulative effects of inadequate nutrition and poor health status. It is a measure of past nutrition condition. The worldwide variation of the prevalence of low H/A is considerable, ranging from 5 percent to 65.

Data Collection and Data Quality Control Measures

To maintain the quality of data questionnaires was prepared in English and translated in to Amharic and again translated to English to ensure consistency and reliable. The data were collected by 4th year five midwifery students by face to face interviewed methods. To ensure the quality data pretest was done in Melkaoda hospital by using 5% of sample size to check validity and reliable. Every day filled data was checked incompleteness and inconsistency by principal investigators.

Data Analysis

To ensure the quality of data, all filled questionnaires were checked incompleteness and inconsistency. Data were entered using Epi Info version 3.5.1 and exported to SPSS version 20.0 for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistical analysis was used to compute frequency, percentage and mean for independent and dependent variables. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to ascertain the association between explanatory variables and outcome. Variables with significant association in the bivariate analysis were entered into multivariate analysis to determine factors associated with malnutrition. Variables with P value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Finally the results were presented in texts, tables and graphs.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from Hawassa University College of Medicine and Health Sciences were taken to Shashemane Referral Hospital administer office and permission was obtained and then a brief explanation of the purpose of the study was explain and individual verbal consent was obtained from the mother or any one with child before starting the interview or taking body measurements. Those respondents who were not willing to participate in the study were not forced to be involved. The respondent was also being informed that all data obtained from them were kept confidential by using coding instead of any personal identifiers and is meant only for the purpose of the study.

Results

Demographic and Socio-Economic Characteristics

From the total planned study subjects, complete response was obtained 384 (91%). Three hundred four (79.2%) of the respondents were female and 80 (20.8%) of the respondents were males. Three hundred forty eight (90.6%) respondent were married. Majority of respondents were Oromo ethnic group 225 (58.6%). The study subjects religious were 142 (37%) were Muslim and 127 (33%) were protestant. Family size of the study subjects were 148 (38.5%) had less than five family size while 263 (68.5%) of participants had under five child. Educational status of the participants were 130 (33.9%) of mothers and 45 (11.7%) of fathers had no formal education. About 144 (37.5%) of mothers and 144 (37.5%) of fathers were completed grade 1-8 (Tables 1 and 2).

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex of respondent | Male | 80 | 20.8 | |

| Female | 304 | 79.2 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 348 | 90.8 | |

| Divorced | 28 | 7.3 | ||

| Widowed | 8 | 2.1 | ||

| Ethincity | Oromo | 225 | 58.6 | |

| Amhara | 53 | 13.8 | ||

| Wolayta | 47 | 12.2 | ||

| Tigray | 28 | 7.3 | ||

| Gurage | 28 | 7.3 | ||

| Religion | Muslim | 142 | 37 | |

| Protestant | 127 | 33 | ||

| Orthodox | 107 | 27.9 | ||

| Catholic | 8 | 2.1 | ||

| Family size | <5 | 148 | 38.5 | |

| >5 | 236 | 61.5 | ||

| Number of under 5 | 1 | 263 | 68.5 | |

| 2-3 | 121 | 31.5 | ||

| Maternal education | Non formal education | 130 | 33.9 | |

| Grade 1-8 | 144 | 37.5 | ||

| Grade 9-12 | 62 | 16.2 | ||

| Diploma | 40 | 10.4 | ||

| Degree and above | 8 | 2.1 | ||

| Paternal education | Non formal education | 45 | 11.7 | |

| Grade 1-8 | 144 | 37.5 | ||

| Grade 9-12 | 119 | 31 | ||

| Diploma | 51 | 13.3 | ||

| Degree and above | 25 | 6.5 | ||

| Occupation of mother | Housewife only | 243 | 63.3 | |

| Farmer | 2 | 0.5 | ||

| Merchant | 81 | 21.1 | ||

| Gov.t employee | 48 | 12.5 | ||

| Daily labour | 10 | 2.6 | ||

| Occupation of father | Farmer | 113 | 29.4 | |

| Merchant | 129 | 33.4 | ||

| Gov t employee | 99 | 25.8 | ||

| Private business | 35 | 9.1 | ||

| Daily labour | 4 | 1 | ||

| Monthly income of the family | <1254 | 90 | 23.4 | |

| >1254 | 294 | 76.6 | ||

| Ownership of livestock | Yes | 195 | 50.8 | |

| No | 189 | 49.2 | ||

| Type of livestock | Cow milk | 126 | 32.8 | |

| Oxen or bulls | 34 | 8.9 | ||

| Hen | 20 | 5.2 | ||

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics under five children families

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex of child | Male | 184 | 47.9 |

| Female | 200 | 52.1 | |

| Child age | 6-11 | 66 | 17.2 |

| 12-23 | 124 | 33.1 | |

| 24-35 | 100 | 26.4 | |

| 36-47 | 65 | 15.8 | |

| 48-59 | 31 | 6.9 | |

| Place of delivery | Home | 106 | 27.6 |

| Health institution | 278 | 72.4 | |

| Gestational age at birth | <9 month | 33 | 8.6 |

| At 9 month | 184 | 47.9 | |

| >9 months | 167 | 43.5 | |

| Type of birth | Single | 279 | 98.7 |

| Twin | 5 | 1.3 | |

| Still breast feed the child | Yes | 234 | 60.9 |

| No | 150 | 39.1 | |

| Reason for not breast feed | Maternal health problems | 8 | 2.1 |

| Refusal of child | 136 | 35.4 | |

| Maternal pregnancy | 6 | 1.6 | |

| Diarrhea | Yes | 75 | 19.5 |

| No | 309 | 80.5 | |

| Frequency of diarrhea per 2 week | 1 episode | 37 | 9.6 |

| 2 episode | 38 | 9.9 | |

| Fever | Yes | 34 | 8.9 |

| No | 350 | 91.1 | |

Table 2: Characteristics of children age 6-59 months

Characteristics and Caring Practice of Children

Among the children 6-59 months of age 124 (33.1%) and 66 (17.2%) children were found in the age groups of 12-23 and 6-11 months respectively. The mean ages of children were 24.4 with SD of 13.The study subjects 278 (72.4%) children were delivered at health facilities and 106 (27.6%) of children were delivered at home. Regarding breastfeeding 234 (60.9%) of children were still breast feeding at the time of survey. The magnitude of common childhood illness 75 (19.5%) of children had diarrhea in the last two weeks before study conducted.

Child Caring Practice

The study subjects 285 (74.2%) were initiated breast feeding practice immediately after birth. In addition to initiation of breastfeeding practice and 40 (10.4%) were received pre lactation food or fluids like Butter 14 (3.6%) and milk 2 (1%). Two hundred eighty five (74.2%) children were exclusively breastfeed until six month. However, 89 (23.2%) of children were mixing feeding started. From the participants 346 (90.1%) of children were immunized and 38 (9.9%) of children were not immunized (Table 3).

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiation of breast feeding to the child | Immediately | 285 | 74.2 | ||

| After a hour | 73 | 19 | |||

| After a day | 26 | 6.8 | |||

| Child pre lactation food or fluid | Yes | 40 | 10.4 | ||

| No | 344 | 89.6 | |||

| Type of pre lactation food or fluid | Butter | 14 | 3.6 | ||

| Milk | 2 | 1 | |||

| Water | 16 | 4.2 | |||

| <6 months | 89 | 23.2 | |||

| Complementary food started | 6-12 months | 285 | 74.2 | ||

| >12 months | 8 | 2.1 | |||

| 3-5 times | 76 | 19.8 | |||

| 6-8 | 52 | 13.6 | |||

| Immunization | Yes | 346 | 90.1 | ||

| No | 38 | 9.9 | |||

Table 3: Children caring practice

Maternal Characteristics

The age of mothers were 32.1 (± 6.7SD) years and mean age of first and youngest children birth were 29.8 (± 6.6SD) and 30.1 (± 6.8SD), respectively. Almost 321 (83.6%) of mothers did not take extra food during pregnancy. About 303 (78.9%) of mothers visited health facilities for ANC during pregnancy. Regarding the use of family planning 279 (72.7%) mothers were used family planning and majority of mothers 193 (50.3%) were used injectable contraceptives (Table 4).

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of mother in years | 20-29 | 147 | 38.3 | |

| 30-39 | 152 | 39.6 | ||

| 40-49 | 85 | 22.2 | ||

| Extra food during pregnancy | Yes | 63 | 16.1 | |

| No | 321 | 83.9 | ||

| Visit health facility | Yes | 303 | 78.9 | |

| No | 81 | 21.1 | ||

| Family planning used | Yes | 279 | 72.7 | |

| No | 105 | 27.3 | ||

| Type of family planning used | Injectable | 193 | 50.3 | |

| Implant | 38 | 9.9 | ||

| Pills | 58 | 15.1 | ||

| Condom | 2 | 0.5 | ||

Table 4: Under five children’s maternal characteristics

Environmental Health Characteristics of Households

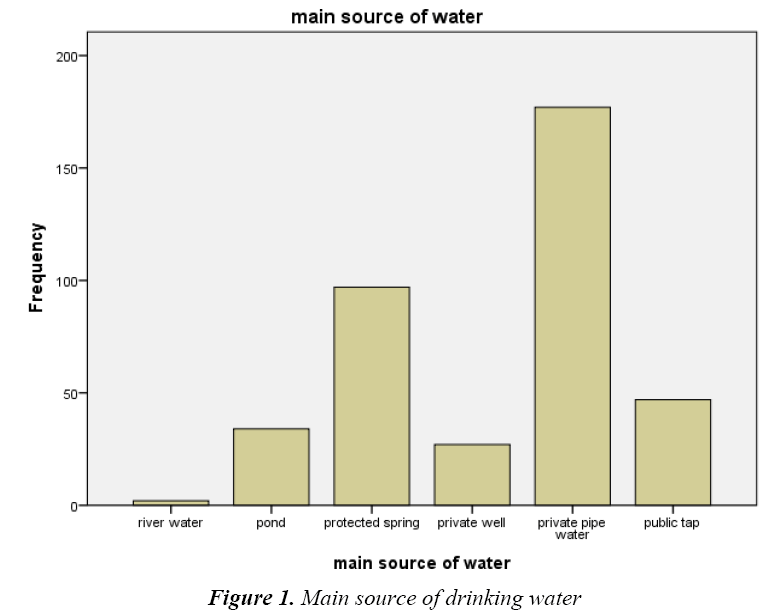

The main source of drinking water used by households were 177 (46.1%) private pipe water, 97 (25.3%) protected spring, 47 (12.2%) public tab, 34 (8.9%) pound, 27 (7%) private well and 2 (0.5%) river water. The study subjects 204 (53.1%) of households were required greater than 50 liters of water per day. The participants 142 (37%) of Households were treat water to make it safe to drink. Concerning about toilet facilities, majority of households 382 (99.5%) had latrine. In this study, wooden slap of latrine 167 (43.5%) were the most commonly being utilized and almost all households were wash hand after toilet, especially by using soap. Regarding waste disposal system 129 (33.6%) and 100 (26%) households were dispose garbage in a pit and open field respectively (Figure 1 and Table 5).

| Variables | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of water used per day | <50 | 204 | 53.1 |

| >50 | 180 | 46.9 | |

| Treat water by any means | Yes | 142 | 37 |

| No | 242 | 63 | |

| Availability of latrine | Yes | 382 | 99.5 |

| No | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Materials used to wash hands after toile use | Water only | 94 | 24.5 |

| Sometimes with soap | 139 | 36.2 | |

| Always with soap | 102 | 26.6 | |

| Sometimes with ash | 49 | 12.8 | |

| Method of waste disposal | Open field | 100 | 26 |

| In apit | 129 | 33.6 | |

| Common pit | 70 | 18.2 | |

| Composing | 24 | 6.3 | |

| Burning | 61 | 15.9 |

Table 5: Environmental health characteristics of households

Magnitude of Malnutrition among Children Aged 6-59 Months

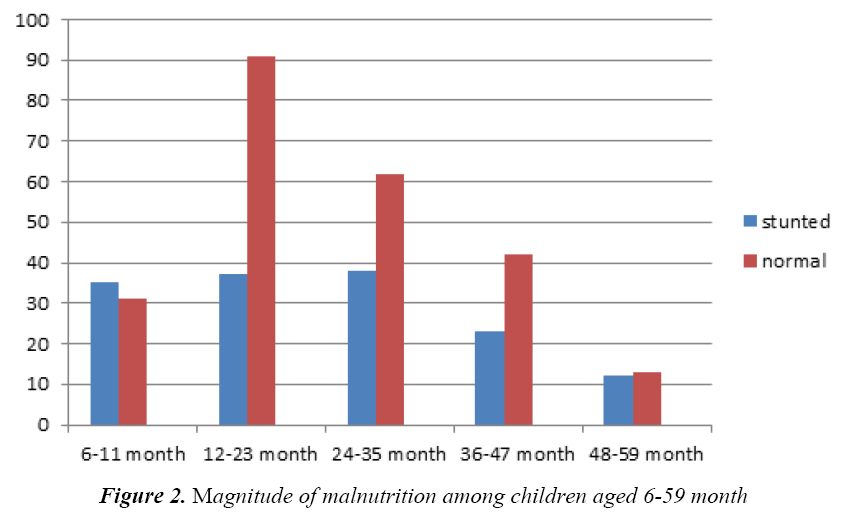

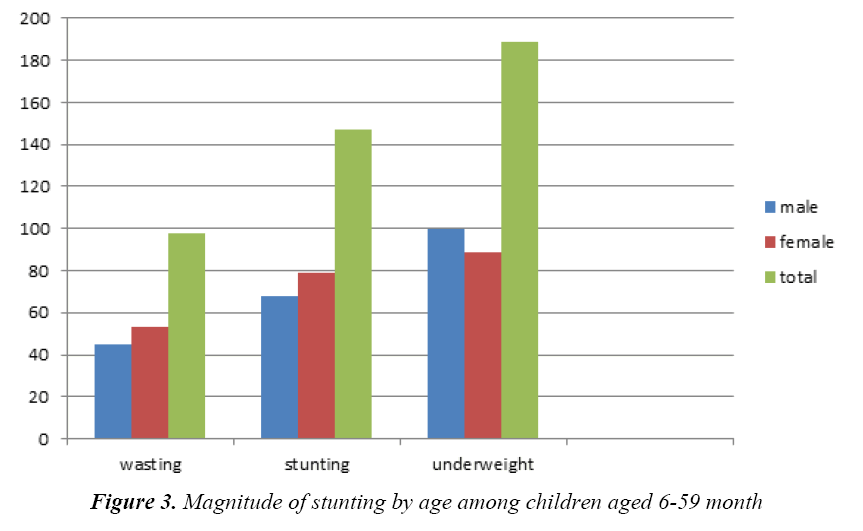

The overall magnitude of malnutrition of children among children 6-59 months in study area were 38.3% stunted, 49.2% were underweight and 25.5% were wasted (Figure 2).The highest magnitude of malnutrition children aged 6-59 months were seen in females. Compared with age groups, the highest magnitude of stunting was children age 24-35 months (9.9%) followed by children aged 12-23months (9.6%). However, the lowest magnitude of stunting was seen in children aged 48-59 months (3.1%) (Figure 3).

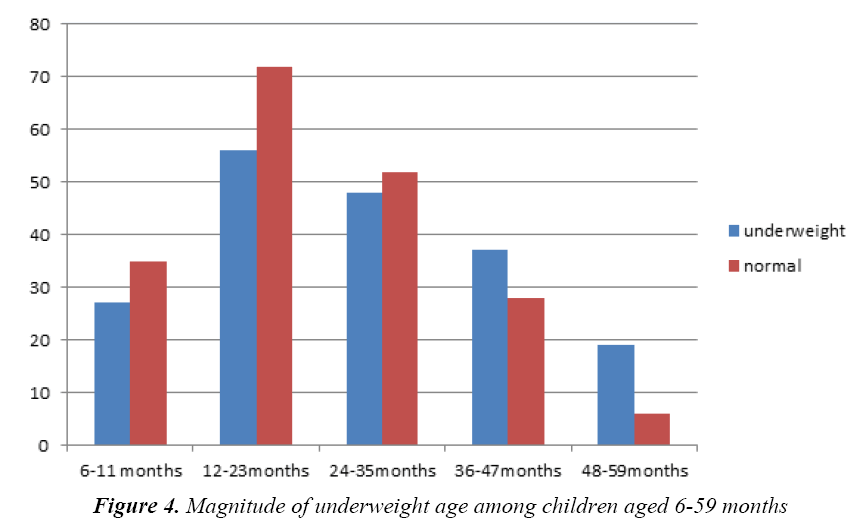

The highest magnitude of underweight was seen in children aged 12-23 months with magnitude of 14.5%. However, the lowest magnitude of underweight was seen in children aged 48-59 months with magnitude of 4.9% (Figure 4).

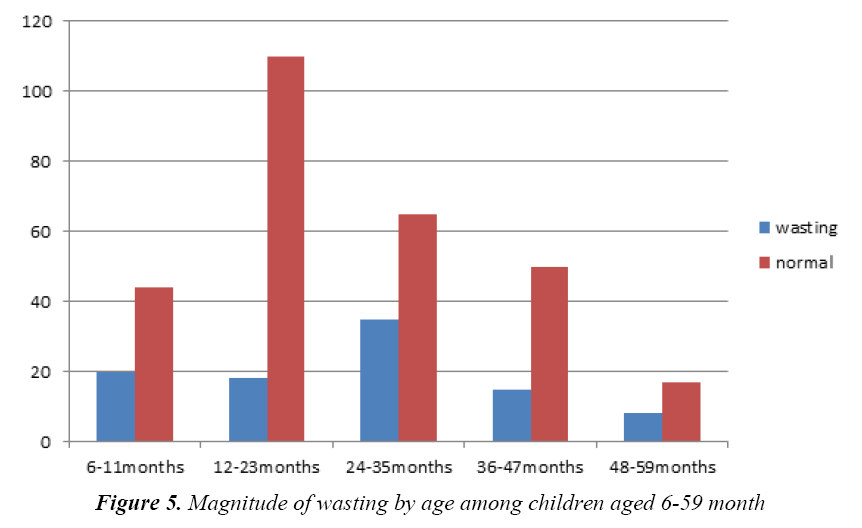

The highest magnitude of wasting was seen children aged 24-35 months with 9.1% magnitude. The lowest magnitude of wasting was seen in children aged 48-59 months with magnitude of 2% (Figure 5).

Factors Associated with Malnutrition among Children Age 6-59 Months

Associated factors of stunting: Children whose mother were completed grade 9-12 were 0.3 times less likely to be stunted than children whose mother had non-formal education (AOR=0.3 (0.14,0.6) 95% CI) (Table 6).

| Variable | Stunting | COR 95% CI | AOR95% CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||||||

| Educational status of mother | ||||||||||

| Grade1-8 | 52 | 92 | 1.42 (0.7,2.74) | 0.38 (0.18-0.66) | ||||||

| Grade9-12 | 34 | 28 | 3 (1.2,4.5) | 0.3 (0.14,0.6) * | ||||||

| Diploma and degree | 6 | 7 | 2.15 (1.32,3.76) | 0.5 (0.24,0.51) | ||||||

| Non formal education | 37 | 93 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Child age in months | ||||||||||

| 6-11 | 35 | 27 | 1.4 (1,1.6) | 2.2 (1.6,6.1) | ||||||

| 12-23 | 37 | 91 | 0.44 (0.3,0.43) | 2.3 (1.18,4.5) | ||||||

| 24-35 | 38 | 62 | 0.66 (0.28,0.85) | 2.2 (1.17,4.3) | ||||||

| 36-47 | 23 | 42 | 0.6 (0.2,0.98) | 1.8 (1.3,3.4) | ||||||

| 48-59 | 12 | 13 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

Table 6: Associated factors of stunting

Associated factors of underweight: Children 36- 47 months of age were about 0.2 times less likely underweight as compared to other children (AOR=0.2 (0.07,0.6); 95% CI).Children who eat atmit or bula or soup as a complementary food were 2.8 times more likely underweight as compared breast feeding (AOR=2.8 (1.3,5); 95% CI) (Table 7).

| Variable | Underweight | COR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||||||

| Child age | |||||||||

| 6-11 | 27 | 35 | 0.24 (0.15-1.5) | 0.7 (0.4,1.4) | |||||

| 12-23 | 56 | 72 | 0.25 (0.14-1.4) | 0.9 (0.43,2.3) | |||||

| 24-35 | 48 | 52 | 0.29 (0.2-1.1) | 0.45 (0.23,1.6) | |||||

| 36-47 | 37 | 28 | 0.41 (0.12,0.75) | 0.2 (0.07,0.6)* | |||||

| 48-59 | 19 | 6 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Type of complementary food | |||||||||

| Cow milk | 80 | 77 | 1.45 (0.85,3.8) | 3 (1,6) | |||||

| butter | 3 | 6 | 0.7 (0.5,4.4) | 0.6 (0.1,1.5) | |||||

| Sugar solution | 6 | 8 | 1.05 (0.5,1.65) | 1 (2.3,3.43) | |||||

| Formula milk | 30 | 30 | 1.4 (0.84,1.2) | 0.64 (1.23,2.8) | |||||

| Bula soup | 54 | 30 | 2.5 (1.25,3.6) | 2.8 (1.3,5)* | |||||

| Breast feeding | 40 | 56 | 1 | 1 | |||||

*p<0.05 is significance

Table 7: Associated factors of underweight

Discussion

In this study the magnitude of stunting, underweight and wasting were about 38.3%, 49.2% and 25.2%, respectively. This finding is lower than compared to the study were conducted different parts of the county parts especially stunting, but lower than wasting [19-21]. However, the finding of this study also slightly lower than the study was conducted in the Gimbi district, 32.4% stunting, 23.5% underweight and 15.9% wasting [22]. But, the finding of this study is revealed that magnitude of stunting and wasting was higher as compared with study of west Gojam zone [23]. Similarly, the finding of this study is revealed Magnitude of malnutrition also higher than study conducted on Beta-Israel children in Amhara region, 37.2%, 14.6% and 4.9% of children age 0-59 month were stunted, underweight and wasted, respectively [24]. This finding also slightly higher than national prevalence of malnutrition [16]. Magnitude of underweight higher but magnitude of stunting was low as compared to study done in Bangladesh, 40%and 42% of children were underweight and stunting , respectively [25]. The magnitude of malnutrition higher in this finding as compared to study conducted in Mongolia, the magnitude of stunting, wasting and underweight were 15.6%, 1.7% and 4.7%, respectively. The present finding showed that, children aged 36-47 times less likely underweight as compared to other age group children[AOR=0.2 (0.07,0.6); 95% CI]. Children who eat soup as a complementary food were 2.8 times more likely underweight as compared breast feeding [AOR=2.8 (1.3,5); 95% CI]. Children whose mother were completed grade 9-12 were 0.3 times less likely to be stunted than children whose mother had non-formal education [AOR=0.3 (0.14,0.6)95%CI]. In the other studies 6.35 months age of children were associated with stunting, but not underweight [2].

Conclusion and Recommendation

The magnitude of stunting, underweight and wasting were about 38.3%, 49.2% and 25.2%, respectively. This study was revealed that, magnitude of malnutrition was high than the regional and national figures found from Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey 2011 national reports. Educational status of mother and age of child age were the only variable that was significantly associated with chronic malnutrition (stunting). However, child age and type of complementary food for the child were significantly associated with underweight. Community based nutrition education program need to be established to tackle the problem of malnutrition at community level. Nutrition education by health extension works need to be strengthening to improving the feeding practice of parents on appropriate children feeding.

Acknowledgement

The authors’ like to acknowledge Hawassa University College of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Nursing and Midwifery for giving me this opportunity. The authors’ would like to say thank you to the data collectors who participated in the data collection process.

References

- UNICEF, WHO. World Bank Group joint child malnutrition estimates Levels and trends in child malnutrition 2015.

- Asfaw M, Wondaferash M, Taha M, et al. Prevalence of under nutrition and associated factors among children aged between six to fifty nine months in Bule Hora district, South Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 41.

- Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, et al. For the child health epidemiology reference group of WHO and UNICEF. Global, regional and national causes of child mortality: An updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 2012; 379: 2151–2161.

- Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, et al. For the maternal and child under nutrition study group. Maternal and child under nutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 2008; 371: 243–260.

- Rayhan I, Sekandarm M, Khan H. Factors causing malnutrition among under five children in Bangladesh. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 2006; 5: 558-562.

- Glewwe P, Miguel EA. the Impact of child health and nutrition on education in less developed countries. In: Paul Schultz T, John S, editors. Hand book of Development Economics. 4. Oxford: Elsevier BV 2007: 3561–3606.

- Abuya BA, Ciera JM, Kimani-Murage E. Effect of mother’s education on child’s nutritional status in the slums of Nairobi. BMC Pediatr 2012; 12: 80.

- Joosten KFM, Hulst JM. Prevalence of malnutrition in pediatric hospital patients. Curr Opin Pediatr 2008; 20: 590-596.

- Janevic T, Petrovic O, Bjelic I, et al. Risk factors for child hood malnutrition in Roma settlements in Serbia. BMC Public Health 2010; 10: 509.

- Adeba A, Garoma S, Fekadu H, et al. Prevalence of wasting and its associated factors of children among 6-59 months age in Guto Gida district, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. Food Science and Quality Management 2014; 24.

- Bhutta ZA. What works Interventions for maternal and child under nutrition and survival. Lancet 2008; 371: 417-440.

- UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates 2016 edn.

- Solomon A, Zemene T. Risk factors for severs acute malnutrition in children’s under the age of five: A case control study. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development 2008; 22.

- Belachew T. Human nutrition for health science students, lecture note series. Jimma University 2007.

- Letham GM. Human nutrition in developing countries FAD of UN, Rome 2008.

- UNICEF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011.

- Central Statistical Agency (Ethiopia) Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 2014.

- Mekonnen A. Ethiopian journal of health development 2008; 16.

- Birhanu MM. Systematic reviews of prevalence and associated factors of under-five malnutrition in Ethiopia: Finding the evidence. International Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences 2015; 4: 459-464.

- Demissie S, Worku A. Magnitude and factors associated with malnutrition in children 6-59 months of age in pastoral community of Dollo Ado district, Somali region, Ethiopia Science J Public Health 2013; 1: 175-183.

- Kebede E. Prevalence and determinants of child malnutrition in Gimbi District 2007.

- Teshome B, Kogi-Makau W, Getahun Z, et al. Magnitude and determinants of stunting in children under five years of age in food surplus region of west Gojam zone. Ethiop J Health Dev 2006; 23: 98-106.

- Asres G, Eidelman AI. Nutritional assessment of Ethiopian Beta-Israel children: A cross-sectional survey Breastfeed Med 2011; 6: 171-176.

- Siddiqi NA, Haque N, Goni MA. Malnutrition of under-five children: Evidence from Bangladesh. Asian J Med Sci 2011.

- Otgonjargal D, Bradley A, Woodruff F, et al. Nutritional status of under-five children in Mongolia. Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences 2012; 3: 341-349.